Cooking Fireplaces and Bake Ovens

Fireplace, oven and article by Jim Buckley

|

The difference in New England and in other colder climates was that the ovens, instead of being out doors and built of stone or adobe, were usually built inside and built with brick and usually associated with cooking fireplaces.

Beyond that there was great variety. I have poked my head into many old ovens and read what I could find on the subject and came to the conclusion that building a masonry oven was an "imprecise science" in the words of Peter Rose who wrote one of the best articles, "Baking in a Beehive" published in 1985 in Americana. Apparently masonry ovens are fairly forgiving and/or the cooks didn't complain much and were able to adjust to what must have been very different firing procedures and firing times from one oven to the next. The ovens discussed here are called "black ovens" which means the fire is in the same oven chamber where the food is cooked. Ovens can be fired very hot like 1,200 degrees F for pizza or just barely kept warm to warm plates for supper. Many early residential ovens were fired every day - hot in the morning to prepare fast breads. Then the fire would be swept out and the oven mopped with a damp mop to keep moist to bake bread. And then just kept warm enough, maybe by adding more wood, to prepare soup or roast vegitables for the midday meal. Larger commercial ovens might be fired continuously with the fire pushed to one side or the back to make room for the food. There are "white ovens" which are heated by a fire below the oven or by flue gasses in passageways around the oven as in some masonry heaters, but white ovens are difficult to build so that they get hot enough and are not very common.

|

|

Black Oven "rules" 1) The shape of the oven is ideally like that of an Eskimo igloo - semi-spherical with a tunnel entrance - although many ovens are arched vaults or even square. 2) The oven has to be at least 16" in diameter inside to be useful. An oven three feet in diameter (inside) is a nice size for a residential pizza oven. Most commercial ovens are much bigger. 3) The flue is just inside the oven door or entrance and must be two thirds as high as the top of the dome of the oven. Too low and the oven smokes. Too high and it cools off too fast. 4) The walls must not be too thin (the oven will not stay hot very long) nor too thick (the oven will take too long to get hot). The walls should be at least 8" thick and kept at least 2" away from combustible materials to comply with modern building codes for fireplace fireboxes but three or four inches of that thickness should be insulation. If the oven walls are within a more massive chimney structure, insulate between the oven walls and the rest of the masonry. Otherwise the oven never heats up.

|

____

|

Early American ovens built before 1760 were usually built into the back of big cooking fireplaces. This one, built about 1720 outside a Bucks County, PA roadhouse is about six feet in diameter with the entrance in the back of a twelve foot wide fireplace on the other side of the wall. Notice the "squirrel tail" or "Mohawk" flue passageway over the top of the oven and venting into the fireplace just above the oven entrance which was probably a way to get the oven to heat more evenly and draw better. This style was typical in Colonial America.

|

|

|

After about 1760 ovens were built to one side of the cooking fireplace more like the one at the top of the page, rather than in the fireback, probably because so many cooks caught their hair or clothing on fire reaching over the fire to use the oven.

|

|

One of the most interesting fireplaces and ovens is in the fully restored kitchen in the Governor's House at Williamsburg, VA. Notice the oven behind the cook to the left of the fireplace and the "set pot" just inside the fireplace on the left side and the spits that work by weights and a clockworks-like mechanism to automate the cooking process. This was high tech in 1760!

|

|

____

Reproduction Cooking Fireplace and Bread Oven

|

You might have noticed the red brick firebox. It's regular solid facebrick (no cores) laid in regular Portland cement mortar. They didn't have firebrick in 1760 and my customer didn't like that "ugly yellow firebrick". I told him facebrick couldn't take the thermal shock and would crack and spall, but I couldn't convince him. A year after I built the fireplace he called to tell me how much he enjoyed the fireplace and oven. He said five of the brick in the fireback had cracked and the face had spalled off another one. "It's great", he said. "The fireplace is only a year old and it already looks as if it's 200 years old." Another sort of customer would have had me back out to replace brick six times.

|

|

Superior Clay Ovens are shaped like an Eskimo igloo and come in three sizes. Early American ovens were "periodic ovens". In the morning a fire is built inside the oven to bring it up to temperature and then it is used for baking, cooking and warming all day long until it has cooled down. A simple steel "plug" with a couple of legs and handles to set in front of the opening. Push it in a little and it also blocks the flue. The new 36" oven is large enough to keep a fire in it while cooking.

|

18" Oven Components, courtesy Superior Clay Corp.

|

24" Oven Components, courtesy Superior Clay Corp.

|

36" Oven Components, courtesy Superior Clay Corp.

|

_______

|

Daniel Wing and Alan Scott have written a great book on bread making and oven building entitled "The Bread Builders". It's a definitive work, extensively researched and required reading for anyone planning to build a masonry oven or bake bread in one. Alan Scott was kind enough to help me with some questions I had in writing this article and by letting me use a couple of the pictures from his book.

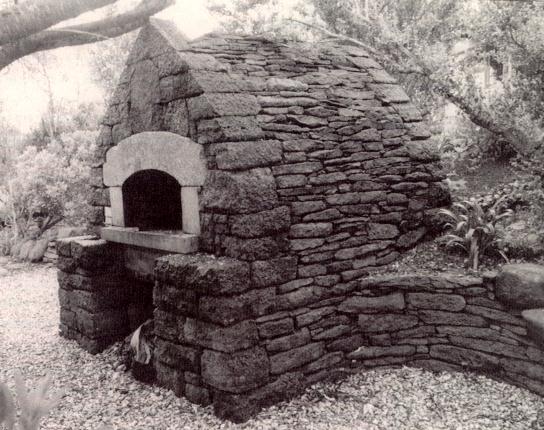

Here is a picture from the book of an oven built by Alan Scott in California in the style of the great stone French ovens.

|

Wing and Scott also explain how to build a fire in an oven. Start the fire under the flue in the front of the oven and gradually move the fire back into the center of the oven as you add fuel.

|

--------

|

Cooking in Your Oven Start the fire in the front of the oven. Add wood when the fire is burning well, and let it burn all the way to the back of the oven. The oven needs to be hot enough - about 1,000 degrees F - which usually takes two or three hours and which you can check with a thermometer. Or you can tell when it's hot enough because the smoke and creosote has burned off the inside of the oven, as in the picture on the right, leaving the oven clean and new-looking inside. When the oven is ready, rake the coals to one side if you are making pizza or rake the coals out and mop the oven with a damp towel if you are baking bread, throw some corn meal on the oven floor and bake right on the hot firebrick. Enjoy! |

Oven hot enough and ready to use. |

Buckley Rumford Fireplaces

Copyright 1996 - 2022 Jim Buckley

All rights reserved.

webmaster